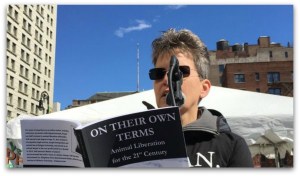

On Earth Day weekend 2016, the Cleveland Animal Rights Alliance invited me to the Cleveland Heights library to offer a presentation (public; free vegan pizza and homemade dishes) on Why We Need an Animal Liberation for the 21st Century.

Rights Alliance invited me to the Cleveland Heights library to offer a presentation (public; free vegan pizza and homemade dishes) on Why We Need an Animal Liberation for the 21st Century.

So we focused on the subtitle and reasons to recharge the phrase animal liberation.

Discussions of rights so often veer into questions about who qualifies. We laud certain animals for demonstrating (often at great cost to the animals themselves) that they can decipher and respond to our cues, or adapt to our domestic environments, or act like us. Our assessments of what animals deserve can trap them again. As Catharine MacKinnon observed more than a decade ago, the model that “makes animals objects of rights in standard liberal moral terms—misses animals on their own terms.”

And lately I’ve been leaning to liberation as our real objective: it evokes those living on nature’s terms, autonomous, free.

leaning to liberation as our real objective: it evokes those living on nature’s terms, autonomous, free.

We can credit Peter Singer as a catalyst for a rising conversation, in the English-speaking world, of animals’ interests and human responsibility. Singer personally underscored this in the New York Review of Books three decades after having published Animal Liberation.

The thing is, the theme of Peter Singer’s 1975 book was not so much liberation as pain management.

To Singer, Animal Liberation promotes a principle that most people already accept: we should minimize suffering. This became the keynote argument for the animal-rights advocacy that followed.

The next slide, quoting Singer at Taking Action for Animals (sponsored by the Humane Society of the United States, 2006), highlights a point of contention. While many advocates agreed with Singer’s opinion that pain sensitivity is what draws our ethical consideration, some wouldn’t wave off our role in their deaths this readily.

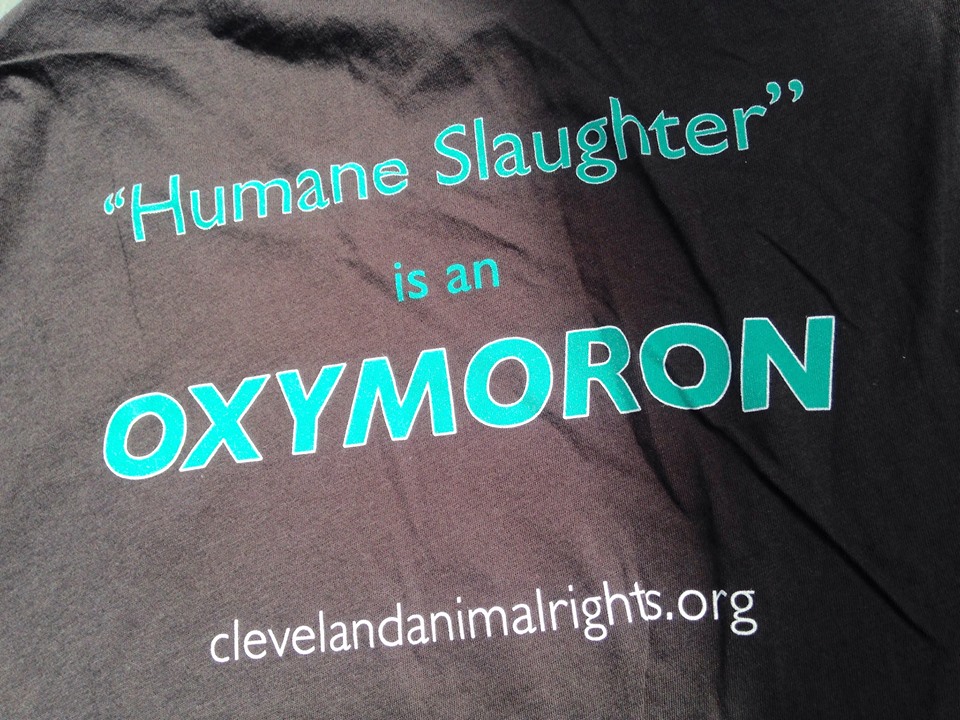

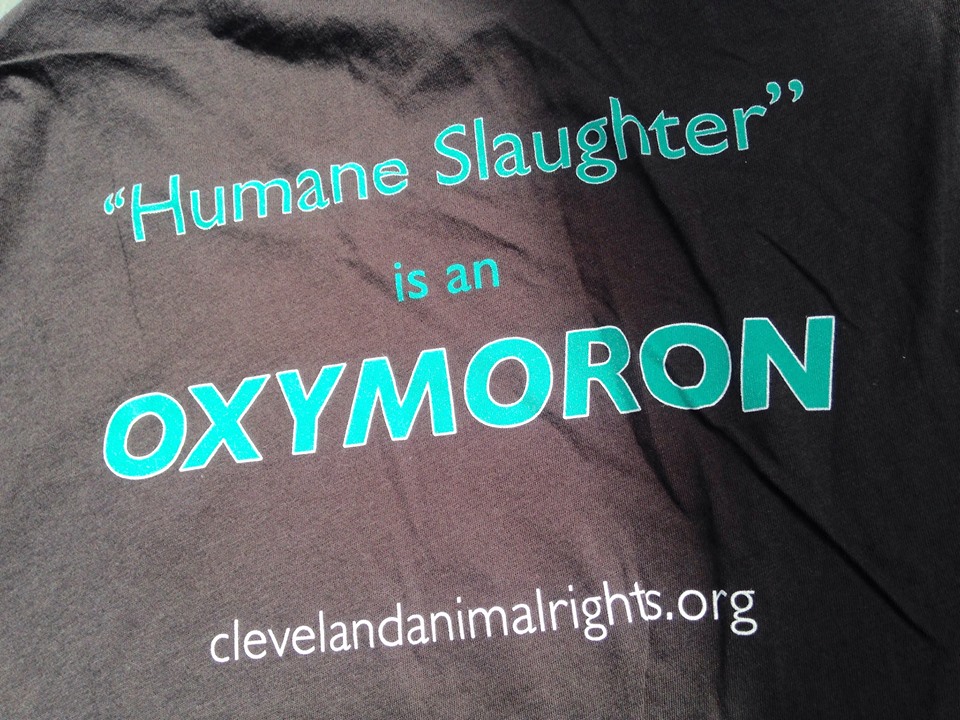

Many advocacy groups followed Singer, though, and never established precepts against killing. The Animal Legal Defense Fund wrote up a Bill of Rights for Animals that accepts killing though livestock must be stunned into unconsciousness prior to slaughter.

Yes!

The idea that causing a conscious being’s death is allowable under the “liberation” banner is bizarre, yet taken for granted in a lot of advocacy. To this day, exposés don’t decry the killing so much as the way animals are killed.

Peter Singer’s “equal consideration” for nonhuman interests will essentially regard animals as containers of pain and pleasure. To cut down on the most suffering, the activist is urged to oppose glaring abuses in animal husbandry. Here’s the point as originally stated in Singer’s Animal Liberation:

To a large extent, even rights advocacy (while taking great pains to differentiate itself from Singer’s brand of utilitarianism) reflects Singer’s model.

– Peter Singer. nybooks.com/articles/2003/05/15/animal-liberation-at-30/

Singer, who wrote Animal Liberation during a key decade for human equality movements, says equal consideration ought to be extended to nonhuman animals. But according to Singer this consideration will only the cover interests we deem similar to those we seek to protect for ourselves.

This might seem logical on its face, but I’m not convinced it’s a fair (or even relevant) way to judge the interests of other animals who have no need for our assessments.

Nautical Dogs and Sterile Deer

Animal-advocacy theorists have presented hypothetical emergencies to justify our preference for putting humans first. Picture a lifeboat that can’t carry an entire group of humans and a dog to safety. Who gets to stay in the boat?

Tom Regan’s Case for Animal Rights came out in 1983. In Regan’s version, the dog loses. Regan assigns a human and dog equal moral significance: we all experience our lives. Yet Regan distinguishes the value of the lives lived by the humans and dog from the value of beings themselves. And then allows the sacrifice of any number of dogs to save the human.

This assertion was repeated quite recently by Gary L. Francione and Anna Charlton, who, in Eat Like You Care: An Examination of the Morality of Eating Animals (2013), say they “will not challenge these widely-shared moral intuitions” that “may tell us that in situations of genuine conflict between humans and animals, humans win. But our intuitions also tell us that in situations in which there is no conflict, we cannot inflict suffering on animals simply because we get enjoyment from doing so.”

Here’s the message the 21st century is sending to animal advocacy: There is hardly any uncontested space on this planet. There are more than seven billion of us, and everywhere, humans are “winning” while everyone else is disappearing.

People now impose contraception on deer so we can  spread ourselves out without having to deal with the “conflict” of animals in our way. Or we oust untamed animals in the name of human rights. In India, a Tribal Rights Bill was introduced to redress discrimination by allocating land to several million indigenous forest-dwellers—while annihilating the region’s last few hundred tigers. Is erasure of tigers acceptable because the tigers would have had less possible sources of satisfaction than the indigenous people? Or does ethical decision-making require a thought process more complex than that?

spread ourselves out without having to deal with the “conflict” of animals in our way. Or we oust untamed animals in the name of human rights. In India, a Tribal Rights Bill was introduced to redress discrimination by allocating land to several million indigenous forest-dwellers—while annihilating the region’s last few hundred tigers. Is erasure of tigers acceptable because the tigers would have had less possible sources of satisfaction than the indigenous people? Or does ethical decision-making require a thought process more complex than that?

Under new global climate patterns, lifeboat scenarios will happen a lot. Environmental crises are unfolding more quickly than could have been predicted when many animal-rights texts were written.

Chapter Nine of On Their Own Terms: Animal Liberation for the 21st Century reviews advocates’ agreement to control the fertility of free-living animals over the years. In 1975, Singer suggested that animals have an interest in our research and development of fertility control over free-living communities.

The assumption that free-living animals might wreck their environment and need us to step in as supervisors matches the claims of administrative officials ready to lower the boom on animals in woods, parks, and fragments of green space. In 2008, when deer were targeted near Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, rights advocate Tom Regan accepted the premise that the local deer must be controlled, but argued that it should be done by pharmaceutical means. The contraceptive substance porcine zona pellucida (PZP), made from the membranes of pig ovaries, triggers the deer’s immune system, forcing the body to attack the deer’s own eggs.

The Swarthmorean, 18 Dec. 2008

Regan’s position startled and disappointed me—for Regan’s book The Case for Animal Rights had urged: “With regard to wild animals, the general policy recommended by the rights view is: let them be!” But support for human-controlled reproduction in free-living communities had precedent in animal-rights legal work. In the 1990s, Gary Francione and Anna Charlton, on behalf of their Animal Law Project at Rutgers, explained their action on behalf of Pity Not Cruelty, Inc. to change deer-control policy in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania:

“We are assisting the plaintiffs in the Lower Merion challenge in the dissemination of information concerning non-lethal methods to decrease any deer/human conflicts, including the possible use of immunocontraception where the deer population can be verified to have increased considerably.”

This presents the deer’s very act of reproducing as a possible situation of true conflict. The stance ignores the obvious—balancing the deer population isn’t up to humans; it’s the role of native carnivores and omnivores.

Today, communities are demanding the systematic spaying of deer.

A liberatory theory ought to call for the neutering of cats (TNR) or to prevent dogs from mating, they already lack the ability to reproduce and raise their young on their terms. Phasing out the breeding of animals as pets would, essentially, put wildcats and wolves off-limits to selective breeding to suit our whims. But contraception for free-living animals is animal control—nothing more, nothing less. Note the importance of distinguishing selectively bred animals from communities of animals who could actually experience autonomy, and shouldn’t be denied that opportunity.

I’ll let the next slide speak for itself.

But for context, let’s talk about how much room we take up on this planet, thanks to some work made available by Californians for Population Stabilization.

Humanity’s mass (we’re the red bar segments in the next chart) has eclipsed the collective weight of all Earth’s free-living land mammals (green segments).

Humanity’s mass (we’re the red bar segments in the next chart) has eclipsed the collective weight of all Earth’s free-living land mammals (green segments).

Add to this the weight of our entourage of purpose-bred animals (blue segments).

Witness our expansion as we press the rest of Earth’s bio-community off the chart.

Witness our expansion as we press the rest of Earth’s bio-community off the chart.

Can we so readily accept the claim of “too many of them”?

Shoppers gonna shop. Can we accept that some (really fancy) husbandry improvements support the liberation mission, sort of?

OK, let’s look at an e-mail I received from Whole Foods Market in London on 15 April 2016, just one week before Earth Day.  It says…

It says…

“While organic dairy cows yield on average a third less than intensive production, the benefits of organic dairy are huge. In order for a dairy to achieve organic certification the herd must be pasture-grazed throughout the grazing season.”

The cows are on pastures (read: sprawl – and let’s explain it as such to our shopping friends), and they only “yield” a third of what densely confined cows produce. So, if all the cow’s milk shoppers switched to organic, they’d effectively demand three times as many cows? Look at these cows.

The next slide joins the two above advocacy positions: (a) constricting the populations of free-living animals, and (b) allocating more space to animal husbandry. Both positions, and certainly the two combined, support human claims to habitat and, in turn, the disappearing of the untamed.

Both campaigns arguably advance ye olde humane-treatment principle “based on values that most people accept” but neither supports true animal welfare. The vegan response to these campaigns is non-participation. (That doesn’t mean doing nothing! We need to give our active support both to vegan-organic farming and predator coexistence initiatives.)

Peter Singer and Jim Mason, in The Way We Eat: Why Our Food Choices Matter, suggest animal husbandry could be a beneficial system for the animals involved. Hogwash. The hills were the habitat of wolves and wildcats before we came in with our animal husbandry.

Peter Singer and Jim Mason, in The Way We Eat: Why Our Food Choices Matter, suggest animal husbandry could be a beneficial system for the animals involved. Hogwash. The hills were the habitat of wolves and wildcats before we came in with our animal husbandry.

As for an incremental step on the way to rights for animals, let’s be clear: no improvement in the conditions for purpose-bred animals cuts the mustard. The more connected to nature the farm is, the more reasons for the farm owner to set traps or call the “nuisance control” professionals.

Free-living animals lose where they’re overlapped by controlled ones, as the owners continually introduce problems into habitats.

No authentic rights await purpose-bred animals; the concept is an absurdity we can accept only as long as we accept purpose-breeding.

Cultivating Active Respect

One rights scholar has said: “If we are going to make good on our claim to take animal interests seriously, then we have no choice but to accord animals one right: the right not to be treated as our property.” Will this resolve all the problems?

Reindeer were domesticated back in 14000 BC; dogs were bred from wolves about 13000 BC—long before modern conceptions of rights and property.

Because domination is a deeper, broader problem than property status, we’d best think of abolitionism—the call to stop treating animals as commodities—as a component of animal liberation. We’ve got to get over our practice of warring against other beings, displacing them, hijacking their reproduction and demolishing their spaces. Authentic animal-liberation theory conceives of affirmative action to facilitate animals’ flourishing on their own terms. This means cultivating active respect for animals’ connections with their own communities, for their interests in the climate, in the land, water, and air they require to experience freedom.

And while the interest in shifting other animals’ legal status from property to person is worthwhile, the outcome will be limited if we base our claims on their remarkable abilities to adapt to human environments. Or if we focus on pain control.

And while the interest in shifting other animals’ legal status from property to person is worthwhile, the outcome will be limited if we base our claims on their remarkable abilities to adapt to human environments. Or if we focus on pain control.

The argument for nonhuman personhood, in the 21st century, will defend the life experiences for which animals themselves evolved, free from our assessments or supervision.

Thank you . . .

to Cleveland’s vegan community for encouraging this exploration of our movement and the writing of the book itself. Having a launch date helped to move the new work from a computer file to a book! Bill, thank you for choosing the graph slide and explaining its elements during the presentation. Thanks to all our animal writers, including those not mentioned and those critiqued here, for their contributions to the advocacy dialogue. This writing is not an attempt to compete or compare. It’s intended, in the vegan spirit of collective progress, to help refine our wayfinding, knowing that involves dynamic and sometimes knotty discussions.

Photos of the Earth Day Celebration and book launch in Cleveland Heights courtesy of the Cleveland Animal Rights Alliance. THANKS TO ARKIVE.ORG FOR OFFERING A HUB FOR PHOTOgraphers of animals in Habitat, and encouraging the sharing of these images. Encampments meme: Tiffany Warner on PINTEREST, Pinned from KnowYourMeme.Com

Rights Alliance invited me to the Cleveland Heights library to offer a presentation (public; free vegan pizza and homemade dishes) on Why We Need an Animal Liberation for the 21st Century.

Rights Alliance invited me to the Cleveland Heights library to offer a presentation (public; free vegan pizza and homemade dishes) on Why We Need an Animal Liberation for the 21st Century. leaning to liberation as our real objective: it evokes those living on nature’s terms, autonomous, free.

leaning to liberation as our real objective: it evokes those living on nature’s terms, autonomous, free.

spread ourselves out without having to deal with the “conflict” of animals in our way. Or we oust untamed animals in the name of human rights. In India, a Tribal Rights Bill was introduced to redress discrimination by allocating land to several million indigenous forest-dwellers—while annihilating the region’s last few hundred tigers. Is erasure of tigers acceptable because the tigers would have had less possible sources of satisfaction than the indigenous people? Or does ethical decision-making require a thought process more complex than that?

spread ourselves out without having to deal with the “conflict” of animals in our way. Or we oust untamed animals in the name of human rights. In India, a Tribal Rights Bill was introduced to redress discrimination by allocating land to several million indigenous forest-dwellers—while annihilating the region’s last few hundred tigers. Is erasure of tigers acceptable because the tigers would have had less possible sources of satisfaction than the indigenous people? Or does ethical decision-making require a thought process more complex than that?

Humanity’s mass (we’re the red bar segments in the next chart) has eclipsed the collective weight of all Earth’s free-living land mammals (green segments).

Humanity’s mass (we’re the red bar segments in the next chart) has eclipsed the collective weight of all Earth’s free-living land mammals (green segments).

Witness our expansion as we press the rest of Earth’s bio-community off the chart.

Witness our expansion as we press the rest of Earth’s bio-community off the chart. It says…

It says…

Peter Singer and Jim Mason, in The Way We Eat: Why Our Food Choices Matter, suggest animal husbandry could be a beneficial system for the animals involved. Hogwash. The hills were

Peter Singer and Jim Mason, in The Way We Eat: Why Our Food Choices Matter, suggest animal husbandry could be a beneficial system for the animals involved. Hogwash. The hills were

And while the interest in shifting other animals’ legal status from property to person is worthwhile, the outcome will be limited if we base our claims on their remarkable abilities to adapt to human environments. Or if we focus on pain control.

And while the interest in shifting other animals’ legal status from property to person is worthwhile, the outcome will be limited if we base our claims on their remarkable abilities to adapt to human environments. Or if we focus on pain control.

I’d love for you to read it and review it. Writing a review will be the single most helpful thing you can do to support this work, beyond reading it. Keep in mind that this is a book by an indie vegan author, not an e-pub ninja; so don’t expect technical perfection on the first go. The e-publication phase has been much more difficult than I’d expected. The information technology-loving Cathy Burt has stepped up at the eleventh hour to work out a few glitches, although, given our time limitations, a paragon of production is not a reasonable goal. We’re learning as we go.

I’d love for you to read it and review it. Writing a review will be the single most helpful thing you can do to support this work, beyond reading it. Keep in mind that this is a book by an indie vegan author, not an e-pub ninja; so don’t expect technical perfection on the first go. The e-publication phase has been much more difficult than I’d expected. The information technology-loving Cathy Burt has stepped up at the eleventh hour to work out a few glitches, although, given our time limitations, a paragon of production is not a reasonable goal. We’re learning as we go.